Philipp Geyer was inquisitive about studying how protein ranges within the blood change when an individual tries to drop some pounds. Several years in the past, Geyer, then a postdoctoral fellow, and his colleagues in Matthias Mann’s lab on the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry started to research samples from a weight-reduction plan research, hoping to determine biomarkers that might predict the result of weight-reduction plan and different interventions. They discovered one thing a little bit totally different from what they have been searching for.

While learning the plasma of 1,500 dieters tracked for 14 months, Geyer and his colleagues noticed a lot more variation in protein levels across individuals than inside anyone individual over time. Although some protein ranges modified dramatically in response to dietary intervention, many others remained regular. “For instance, alpha-two microglobin,” Geyer stated. “It’s tenfold totally different between folks, however fully steady inside an individual.”

As patterns emerged from the info, permitting them to select the identical individual at totally different time factors, Geyer and his colleagues started to fret: Could these patterns someday be used to de-anonymize a research participant?

Around the identical time, leaders of a world consortium of proteomics information repositories known as ProteomeXchange have been convening in Amsterdam to debate moral and authorized points in dealing with probably identifiable biochemistry information.

The assembly’s organizer, Juan Antonio Vizcaíno, runs a knowledge repository from his lab on the European Molecular Biology Laboratory–European Bioinformatics Institute, often called EMBL-EBI, within the United Kingdom. Re-identification is “a difficulty that we now have been conscious of for years,” he stated, “however there must be a vital mass to start out discussing it correctly.”

Sharing information is a crucial norm for the proteomics neighborhood. The advantages of openness are paid out in reproducibility, high quality management and maximal use of every information set. Limiting entry to information might impede scientific discoveries and their ensuing therapies and even cures.

Still, even probably the most fervent defenders of open sharing agree {that a} communitywide dialogue about entry to proteomics information is value having.

Earlier this yr, the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, which has performed a major function in making a tradition of openness, printed three articles — two from the Mann lab and one from Vizcaíno and colleagues — on the subject.

ASBMB Today talked to the authors of these papers, the editor who oversaw them, authorized and ethics consultants, and different researchers about what’s and isn’t technically potential right this moment, the dangers and rewards of open proteomics information, and easy methods to make scientific progress whereas nonetheless defending folks’s privateness.

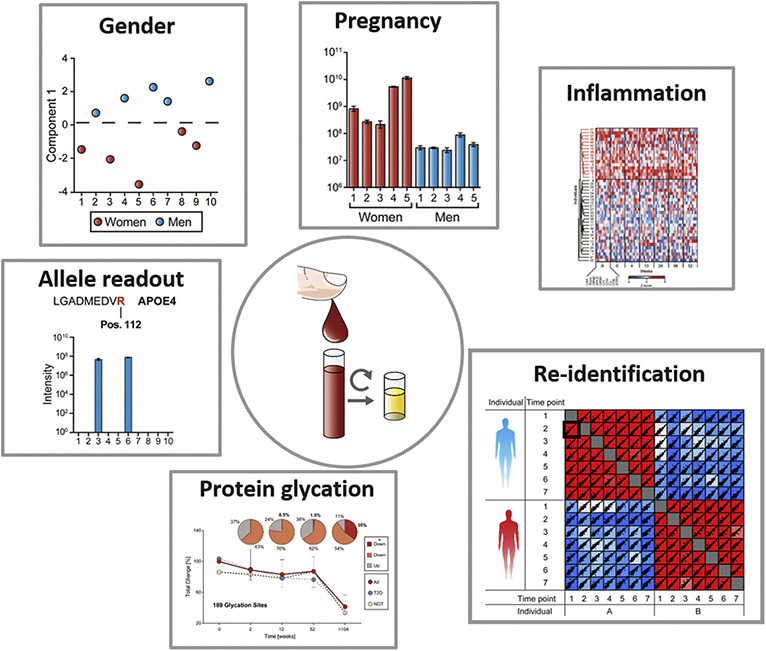

GEYER ET AL./MCP 2021

An evaluation workflow reveals how constant a person’s protein abundance measurements between two time factors (panel A); how that consistency can be utilized to match proteomes to a identified particular person over time (panel B); and the way the staff expanded the evaluation to a whole cohort of contributors (panel C).

What can a proteome reveal?

Whereas genome sequences are extensively thought of recognizable and linkable to a person, most researchers up to now have thought of proteomes extra nameless.

Robert Gerszten, a doctor–scientist on the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, in contrast matching the sample of protein ranges in a medical proteomics experiment to figuring out a blurred picture. If a genome is like a picture of a person’s face, a proteome, due to organic and technical elements, is extra like {a partially} masked picture at decrease decision. It takes longer and prices extra to gather a proteome than a genome, and the depth of protection — the variety of instances an experiment confirms {that a} particular gene or protein is current — is way decrease in mass spectrometry–based mostly proteomics. Due to technical elements in protein preparation and measurement, not all proteins are equally more likely to seem on a spectrum, and absence from the info doesn’t imply {that a} protein shouldn’t be current within the pattern.

“If you’re taking a inhabitants of 1000’s of individuals,” Gerszten stated, “you may clearly discover person-specific signatures in that inhabitants (based mostly on protein focus). You couldn’t have achieved that 5 years in the past. … But I don’t assume that the granularity is sufficient to determine who that particular person might need been in an enormous inhabitants.”

Stefani Thomas, whose lab on the University of Minnesota makes use of proteomics to research candidate biomarkers for most cancers analysis and prognosis, stated the Mann lab’s weight-reduction plan research provides a thought-provoking proof of idea that protein stage alone may be identifiable. However, she stated, to find out traits equivalent to a person’s age, gender or ethnicity utilizing their proteome, researchers would wish to know extra about variability between and inside these teams — just like the analysis her lab does to distinguish between wholesome and illness states.

Researchers don’t know precisely how steady a level-based proteomic signature is over time. The Mann lab’s research adopted contributors for over a yr, which is temporary in comparison with a lifetime. And although weight reduction left most components of the proteomic fingerprint unchanged, the impacts of different physiological occasions aren’t but established.

In addition to a single protein’s presence and abundance, proteomic experiments more and more can reveal one thing that doesn’t change over a lifetime: genetic sequences, within the type of genetically variable peptides.

Proteomics yields sparser sequence info than DNA sequencing. The exome is smaller and topic to extra selective stress than the genome, and protein translation makes synonymous mutations invisible, so much less person-to-person variation exists in proteins than in DNA or RNA. Still, when Geyer and colleagues went again over their information searching for genetic variants, they may certainly determine particular person single-amino-acid variants in some spectra.

GEYER ET AL./MCP 2021

The graphical summary of Geyer and Porsdam Mann’s analysis article in MCP reveals how they used information from inhabitants serum proteomics

research to find out probably figuring out options equivalent to gender, being pregnant standing and allele expression in a cohort.

Geyer received to speaking with Sebastian Porsdam Mann, Matthias Mann’s son, who lately had completed a Ph.D. in bioethics, about how a lot of a danger this posed to contributors — and whether or not the potential of discovery outweighed the chance.

“You have to have top quality information, however so as to scale back identifiability danger, it’s good to do issues to this information to filter out identifiable info. So there’s at all times going to be a trade-off,” Porsdam Mann stated. In addition, there are occasions when with the ability to match a research participant to options of their proteome may very well be useful.

Forensic proteomics

Sometimes researchers by chance make a remark that might have an effect on a research participant’s well being. Philipp Geyer made such a discovery – however the participant was himself.

In the Mann lab, as in different labs dealing with medical samples, specimens arrive stripped of participant title, date of start and different figuring out info. Do the specimens themselves — or, extra importantly, the info the lab uploads to worldwide repositories — carry sufficient info {that a} motivated, proteomics-savvy adversary might hint them again from spectrum to individual?

According to Thomas, a key query stays unresolved: “What is the minimal quantity of information from a proteomic experiment that can be utilized to definitively determine a person?”

Although the medical proteomics neighborhood is simply starting to discover the query, forensic researchers have been making an attempt to find out a solution for years.

Forensic proteomics

Glendon Parker, an adjunct affiliate professor on the University of California, Davis, is one in every of a small variety of scientists working to determine genetically variable peptides for forensic functions; his lab focuses on hair. Inferring a genome, Parker stated, is dependent upon realizing whether or not every change to a peptide is genetic or is attributable to environmental results equivalent to dyes or weathering. That means validating that every candidate genetically variable peptide matches a genotype earlier than utilizing it to deduce genetic info — and in addition that it’s distinguishable from the remainder of the proteome.

Deon Anex, a chemist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory who works on a forensic proteomics venture impressed by Parker’s analysis, frames the query: “Let’s say you’ve gotten a novel peptide, and you then modify one of many amino acids. Is that also distinctive? Or is it now a standard sequence some other place?”

In most circumstances, utilizing the proteome to get a genotype is redundant to long-established strategies based mostly on DNA. However, in some environments, DNA falls to items however proteins survive. According to Anex, forensic proteomics is an efficient fallback for getting genetic info from hair or from brass ammunition cartridges which are inhospitable to DNA. His lab is also engaged on a venture funded by the analysis company of the Office of the U.S. Director of National Intelligence that goals to tug genetic info from the proteins left after bomb blasts. The venture staff has demonstrated that it will probably match proteins from partial fingerprints on objects to the volunteers who dealt with the objects. Now, it’s conducting discipline experiments with lab-made improvised explosive units to find out whether or not these traces are nonetheless recognizable after an explosion.

Based on the variant peptides they detect in a pattern, forensic researchers in Parker’s and Anex’s labs can decide a partial genotype. Using statistical strategies from forensic science, which think about the variety of variants detected and the way widespread each is, researchers can calculate the chances of a false-positive match. Those odds would must be on the order of 1 in 10 billion to determine somebody uniquely on this planet. Parker has a solution to the query Thomas posed; he believes that just some hundred genetically variable peptide calls may very well be sufficient to determine some folks uniquely.

But even when the chances of a false optimistic are very low — even with a genome that unambiguously belongs to a single individual — it’s tough to hint a sequence again to the one that carries it of their physique. Brad Malin is a professor of biomedical informatics at Vanderbilt University. “Uniqueness is inadequate to really determine someone,” he stated. “You want to have the ability to hyperlink that information to another useful resource to get again to their identification.”

He added later, “There have been illustrations that when a corporation or a person is sufficiently motivated, if all the celebrities align, they’ll achieve success. But it requires loads of effort.”

Back within the medical proteomics neighborhood, some researchers say that the chance of a motivated, proteomics-savvy adversary making such an effort is dwarfed by the advantages of open information sharing. Some additionally ask whether or not, in a world the place a lot private info already is collected and bought, the dangers of including proteomics information to the combination might presumably outweigh the advances in science and well being that these information allow.

What’s the hurt?

Malin stated a buddy lately questioned him about why re-identifiability was a priority, asking, “What are the harms? What is it that we’re supposed to fret will go bump within the night time?”

For one proteomics researcher, Michael Snyder, the query is private. Snyder, a Stanford University professor, conducts multiomics research that embrace himself as a research topic; he printed his entire genome, thinly anonymized, years in the past within the journal Cell and has adopted it up with longitudinal transcriptomes, metabolomes and medical assays.

Sporadically through the years, Snyder has heard from individuals who need to share analyses of his well being. Some have had fascinating insights, he stated, however “a few of it’s fairly loony.” Still, he doesn’t consider he has suffered any actual hurt from radical openness about his private biochemistry. Nor is he conscious of different research topics who’ve suffered as a result of their transcriptomic or proteomic information have been printed.

“There’s loads of RNA-Seq information on the market,” he stated. “I problem you to point out me one instance the place that’s been abused.”

He’s proper; no examples of such abuse have been reported. The loudest bumps within the night time come from privateness researchers sounding the alarm about information vulnerability and legislation enforcement businesses utilizing genetic info from opt-in family tree databases — not analysis information. Other potential attackers are up to now a matter of conjecture.

EMBL-EBI

Juan Antonio Vizcaino and his staff run the Proteomics Identification Database,

or PRIDE, out of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Cambridge, UK.

Information in a proteome may give clues about an individual’s well being; American students have envisioned discrimination by well being insurers as a priority, however it’s now illegal for insurers to disclaim protection based mostly on genetic info. Gerszten, the doctor–scientist at Beth Israel, recommended that entrepreneurs hypothetically might mine metabolomic or proteomic databases to search out out about reproductive selections or illness standing. There is little question {that a} marketplace for one of these information exists; based on a cybersecurity agency’s 2019 report, well being information stolen from hospitals promote for about 50 instances the worth of a stolen bank card quantity. (Of course, well being information are simpler to interpret than a proteome, whose significance will not be identified, and so they usually embrace a affected person’s title or different identifiers.)

After revelations that social media and family tree websites can collect and reveal extra info than customers thought they have been sharing, societal conversations round privateness and information sharing have modified up to now decade. Snyder has seen an identical uptick in warning amongst his research contributors since he launched a longitudinal proteomic profiling venture known as iPOP in 2010.

“It did take this shift when folks discovered that Facebook and others have been promoting their information,” Snyder stated. However, he added that he sees contributors on social media “posting some extremely non-public stuff that’s in all probability extra dangerous than proteomics information. Privacy is gone, whether or not you prefer it or not.”

Malin, the bioinformatics knowledgeable, disagreed. “Google’s not taking your entire search queries and throwing them on-line for everyone to see,” he stated. “Privacy shouldn’t be lifeless. You’ve simply shifted who you belief with details about your self.”

From an moral standpoint, Malin stated, any analysis participant whose privateness is compromised has misplaced one thing of worth, even when they undergo no additional penalties. “Whether or not the person was materially harmed … merely the identification could be enough to assert that their privateness had been infringed upon, as a result of they didn’t need that info revealed.”

Lawsuits towards hacked hospitals have argued the identical factor. But researchers say that they, too, have one thing of worth to lose: data that might result in biomedical progress. Broad Institute proteomics director Steven Carr, an MCP deputy editor, stated, “At this time limit, including pointless protections to the supply and use of proteomics information on human samples has the potential to do extra hurt than good.”

What do researchers stand to lose?

In the previous yr and a half, quite a few massive COVID-19 research have illustrated the advantages of information sharing in proteomics. Data units exhibiting viral interaction with human proteins, linking detectable markers to patient outcomes and monitoring immune responses over time have added to an internationally constructed image of how the novel coronavirus works and have been mined by different researchers for additional insights. And this isn’t a brand new phenomenon; based on Snyder, a lot of the annotation of the human proteome has relied on secondary evaluation of publicly accessible information.

FLICKR/EMSL AT PACIFIC NORTHWEST NATIONAL LAB

Detail of a mass spectrometer

Since its launch in 2011, the ProteomeXchange, a consortium of repositories that make proteomic information freely accessible, has printed greater than 24,000 mass spectrometric information units, about 45% of these from human or human-derived cell strains. Thousands of papers have reported new findings based mostly on information within the six repositories that make up the trade.

The discipline was not at all times so open. It took dedication from publishers, funders, information repositories and the Human Proteome Organization to require investigators to make their uncooked information freely accessible to colleagues.

“There was some extent the place only a few folks submitted information to PRIDE or to different assets,” Vizcaíno stated. After a fast change, “Now we’re in a situation that’s principally the alternative.”

Carr and Snyder argue that limits on information sharing to accommodate privateness considerations would danger reversing the sector’s cultural shift. Without easy accessibility to uncooked information, researchers could be unable to verify each other’s work for reproducibility or reanalyze information for follow-up research. Based on how utilization patterns differ between controlled-access and overtly accessible transcriptomics information, Snyder is assured that analysis progress would sluggish if proteomics information have been walled off.

Some proteomics information already are managed as a result of they’re linked to different, extra simply identifiable information equivalent to medical outcomes. Gerszten, whose lab conducts multiomics research of coronary heart illness, stated that they maintain all information from sufferers beneath what he known as digital lock and key. “The skill to say, ‘these units of markers monitor with people who had a greater final result’ … is definitely very precious info,” Carr stated. “It represents no hurt to any particular person. But it does symbolize a pathway to attempt to determine markers that may be helpful for diagnostic functions.”

Gilbert Omenn, a doctor–scientist who directs the University of Michigan’s heart for computational medication, stated, “We need proteomic information to not simply be about advancing instruments of mass spectrometry and different strategies; we would like it to be linked to biomarker growth and medical analysis, and due to this fact we have to translate it to sufferers.”

That objective is coming into view, he stated. It is thrilling for the sector, however “I don’t assume it behooves us to attempt to declare that we’re outdoors the boundaries of accountability.”

Malin believes {that a} main re-identification episode would do extra hurt to researchers than to their contributors. “People are going to scream bloody homicide that they’ll now not belief scientists with their info,” he predicted. “That could be an enormous blow to biomedical analysis.”

Legal necessities, technological options

Laws governing information sharing

HIPAA, GDPR and the Common Rule all have an effect on how scientists in several areas are required to guard, and allowed to share, probably identifiable information.

Concerns about potential injury to the sector motivated Vizcaíno to arrange the Amsterdam assembly of ProteomeXchange leaders and different consultants in 2019.

In a current article in MCP impressed by that assembly, the researchers known as for information entry to turn out to be “as open as potential, as closed as obligatory” to stability analysis transparency and information sharing with privateness considerations. The discipline wants additional analysis into the probability and potential severity of information breaches, they concluded, however even within the absence of such analysis, you will need to start to develop finest practices for dealing with delicate information.

Proteomics databases are designed to make information public and everlasting. After a top quality management verify, PRIDE publishes all the info it receives, typically ready for a corresponding paper to be printed. Here and there through the years, Vizcaíno stated, “We have had just a few circumstances that individuals who had initially submitted information to us have instructed us, ‘We have been instructed by our information officer … that we shouldn’t do that.’”

University information officers try to observe complicated guidelines. In many jurisdictions, client privateness legal guidelines handle what identifiable information could also be shared (see “Laws governing information sharing”), and totally different authorities stability the dangers and rewards of information sharing in another way.

Omenn stated there may be “loads of consideration, a good quantity of angst, and, I feel, reasonably excessive compliance” with authorized necessities for identification safety.

Because coverage modifications slowly and tends to be extra reactive than proactive within the face of technological advances, Malin expects that it could take a significant breach of privateness affecting both hundreds of thousands of individuals or a strong politician to pressure modifications to privateness legal guidelines. When an American coverage known as the Common Rule was revised, a course of that took six years, the businesses concerned within the work determined towards declaring genetic info identifiable.

“The implications of designating organic info as identifiable are fairly breathtaking,” Malin stated. “It would fully shift the way in which that analysis is carried out on this nation.”

Still, he stated, “We’re considerably at a crossroads … it’s potential that the United States goes to have its hand compelled by the European Union.”

Vizcaíno, predicting that re-identification would turn out to be a priority for proteomics, has saved an eye fixed on the DNA and RNA databases that his EMBL-EBI colleagues administer. Often, these directors require that researchers apply for entry to delicate information, offering solely sufficient info to run analyses the labs describe forward of time. Some databases layer in extra measures, equivalent to suppression of extremely identifiable sequences or scrambling of genotypes, to guard info that might determine a person; in the meantime, in a kind of arms race, privateness researchers proceed to report methods to breach these safeguards.

For now, PRIDE and different databases do not need the structure in place to render uncooked proteomics information much less identifiable. If Vizcaíno and his colleagues obtain a request to delete a knowledge set whereas it’s nonetheless beneath overview by editors and reviewers, they’re able to honor that request.

Removing information units after they’re posted, nonetheless, could elevate issues with the ensuing publications. Carr stated, “MCP is not going to settle for papers the place the info can’t be made public.”

Vizcaíno hopes to construct a database that, like databases for genomics, provides managed entry solely to reviewers and researchers who clarify why they should see delicate information, or researchers may be restricted to accessing information that corresponds on to a analysis query. Approaches from genetics, he stated, are sensible, however an funding is required to adapt them to mass spectrometry information codecs. “We are on the very starting of a really lengthy highway.”

Sightlines

Ongoing conversations about proteomic privateness are pushed by what biomarker researcher Stefani Thomas known as “an undercurrent of advances in know-how” and a quicker tempo of proteomic information assortment. That’s excellent news for the sector, she stated, however to appreciate the objective of utilizing the know-how within the clinic, questions on privateness and identifiability have to be resolved. “I feel it’s thrilling that individuals within the discipline are taking a step again and saying, ‘Let’s take a look at this from a broader perspective and guarantee that what we’re doing is moral.’”

Porsdam Mann, the bioethicist, stated, “If you take a look at the historical past of genomics analysis, but additionally different associated fields, you’ll discover that accountable self-regulation early within the sport is among the wisest longer-term investments.”

Carr stated, “The method I view that is in medical phrases. … I feel we ought to be able of watchful ready to see how confidence in potential identification of proteomics information goes.”

Snyder argues that current restrictions on information use are greater than enough. “Until someone will get harmed, I’m unsure I’m so anxious about it,” he stated. “Maybe when someone will get harmed, it’ll all blow up and so they’ll say, ‘Mike, you didn’t foresee this very properly.’ And I’ll say, ‘Yeah — however we received a hell of loads achieved within the meantime.’”

Laws and insurance policies governing information sharing

The Bermuda Principles, established in 1996, supported fast, public information sharing to advance the Human Genome Project. In the years since, considerations about credit score for analysis and about participant identifiability have driven a shift to extra cautious information sharing.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation took impact in 2018. Its protections on information collected in Europe and describing European residents make exceptions for anonymized analysis information, however consultants say that anonymization shouldn’t be properly outlined within the legislation, making it laborious to observe. In a Policy Forum article within the journal Science, authorized students within the U.S. and Europe argued that GDPR protections impeded collaborative worldwide analysis by stopping medical information collected in Europe from being transferred to worldwide collaborators. The limitations to transferring information, they wrote, “look like at odds with the widely research-friendly intent of the GDPR.” According to Vanderbilt bioinformatics professor Brad Malin, till a courtroom guidelines on anonymization necessities, the precise that means of the GDPR for genetic and bioinformatics information will stay ambiguous.

In the United States, information sharing is ruled by a federal coverage, initially adopted in 1991 and since revised, often called the Common Rule. The coverage, which applies to any analysis on human topics carried out or funded by 15 federal departments, is cast by consensus amongst them. The rule exempts information “recorded such that topics can’t be recognized.” As with the GDPR, the Common Rule is complicated and doesn’t spell out whether or not genomes are identifiable or may be anonymized. Health information, equivalent to these produced in medical trials, are also protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, or HIPAA; it, too, makes provision for sharing of de-identified information for analysis functions.

Treatable discoveries

Philipp Geyer, a researcher on the Technische Universität Berlin, had excessive ldl cholesterol beginning in childhood. As a postdoc, whereas establishing a workflow for a big medical trial, he used a pattern of his personal blood as a top quality management. By revealing the amino acid sequence of a peptide from apolipoprotein E, the proteomic information confirmed that Geyer had a variant of the gene linked to persistent excessive levels of cholesterol.

After a lifetime of limiting chocolate and butter, pursuing sport and train regimens, and stubbornly declining pharmacological intervention, Geyer stated, the invention that his downside was genetic gave him a push. “I used to be satisfied, okay, I can’t do something with sports activities or diet, so I actually should take the drug.”

On a statin, Geyer’s ldl cholesterol downside resolved. Monitoring his personal plasma proteome, he watched his apolipoproteins drop. He shared this info with members of his household. “My dad and my brother truly went on statins due to this,” he stated.

Geyer’s discovery is what an ethicist would describe as an incidental discovering. It wasn’t the knowledge he got down to discover, but it surely gave an necessary perception into his well being. And a easy intervention helped Geyer decrease his danger of heart problems.

According to Sebastian Porsdam Mann, a bioethicist and son of PI Matthias Mann who labored with Geyer on a Molecular & Cellular Proteomics article concerning the ethics of medical proteomics research, that is a part of why absolute anonymization of information could not at all times be in a research participant’s finest curiosity. “In the intense, you may actually anonymize it fully,” he stated. “But then you may by no means observe up.”

Steven Carr, proteomics director on the Broad Institute, has skilled the frustration of being unable to observe up; whereas analyzing a lung most cancers pattern, he stated, his lab stumbled throughout a clinically significant discovering. He stated that his staff needed to get in contact with the clinicians who collected the pattern to inform them, “We don’t know who this individual is, however by the way in which, they may have been — or ought to have been — handled with X as a result of they’ve this explicit set of traits of their proteome.” Because of privateness protections, he stated, that form of suggestions was prohibited.

Some incidental findings are much less actionable. For instance, individuals who carry a distinct apolipoprotein E allele than the one Geyer found in his blood are as much as 90% extra more likely to develop Alzheimer’s illness, however the connection shouldn’t be properly understood and somebody who learns they’ve the allele can’t take any motion however wait.

Medical ethicists see a line between actionable and nonactionable info; they are saying that on the whole, if info is actionable, sufferers ought to learn — except, fulfilling the precept of autonomy, they’ve said they like not to learn.

Certain incidental findings may convey info a research participant would favor to not share with others. For instance, doctor–scientist Robert Gerszten talked about that metabolomics research designed to search out coronary heart illness biomarkers additionally may present what drugs an individual is taking or whether or not metabolites of illicit medication are current.